Category: 4e DnD

Awful controllers? It’s the DM’s fault.

It seemed that controllers always had a hard time finding a place around the 4E table for most folks. As an archetype, it was a bit at odds with the other combat roles. Defenders had tools to soak up damage. Leaders were able to crank out the buffs and heals. Strikers poured out the damage. All three of these roles worked in just about any combat encounter.

The controller required other factors to shine, unfortunately meaning certain environmental layouts and monsters were needed to show their effectiveness. Sure they could get a few heavy hitting attacks, but smaller bursts of AoE damage were more common. Even more so, with slows and obfuscating/hindering terrain effects, they needed the space and the right positioning of creatures to really strut their stuff.

I expect that was part of the reason wizards always seemed to under-perform. It’s just that other class types could do things in combat that would work in just about any type of fight. Meanwhile, the wizard was more situational. Sadly, that meant they were really dependent on the DM to provide opportunities to allow them a chance to fully express their abilities and powers. So what are a few things a DM could provide in a fight for a wizard in the party?

Lots of minions – A core aspect of many controller powers are area of effect attacks that do a small pip of damage. Having plenty of targets and more importantly, some clustered up a little, is a decent boon to your party controller. While I don’t use lots of minions in every fight, sometimes it’s good to really fill out the ranks and give that controller plenty of targets to pop.

I try to play the opposition smart, but having those minion types more keen on keeping ranks than spreading out is something I also employ once in awhile. Usually I’ll give that third minion a chance to stick with another creature when I move them around by rolling a d6, just a simple 2 in 6 chance to have a few cluster up. So a few encounters with lots of minions (and the occasional gang of baddies clumping up) is a decent way to give a nod to the party’s controller.

Foes coming in different directions – Having simple battle lines where players can close ranks can make for some solid tactics. But continually allowing this can quickly mean the players can easily manage the engagement and the use of a controller diminishes. When you’ve got multiple monsters piling in from different directions, it’s a great opportunity for that controller type to hinder movement of some targets, giving the other party members time to engage one side first.

Creatures needing to close in – I usually like to mix in ranged attackers in most of my combats. I like to ramp up the threat so that folks not in hand-to-hand still need to worry some. However I lean towards making the melee monsters the more resilient types. And when rolling out creatures in waves, I make sure it’s those melee monsters needing a turn or so to move into the fight. It’s a means to allow the controller to do their stuff and hinder movement of creatures charging in. By tying up one or two targets the group can focus on other monsters first. The group plays smart and everyone has a chance to do something cool.

Traps and hazards that affect both foes and friends – Layering on a wall effect, or some area power hindering movement can add to it’s effectiveness if plopped down next to a few squares of hazardous terrain. Effectively you are adding another 2-3 squares of area under a wizard’s control effects. Give them a chance to do so. A small burst area with flanked by a spiked pit now provides a larger area that’s been locked down.

Sometimes it might lead to monsters preferring to chance a hazard over a spell effect. Does the goblin jump off an elevated platform risking a serious injury? Or do they sit by and let a flaming sphere roll over them? Likely they’ll take the 20’ jump and take their chances. Either way it’s a win/win for the controller.

Take a peek at the PC’s character sheet – Give a look over their powers. Think of some environment that would show off that power. Knowing the abilities of your players can allow you to occasionally craft some fights that allow these powers to be used effectively.

Not every fight has to utilize there tips, but I’d seriously consider giving at least one encounter in a typical delve a few of these characteristics if you’ve got a controller-type in your group. Controllers really need a few wrinkles in your typical encounter makeup to shine. So once in awhile, try to oblige and allow them to enjoy that choice they made playing the wizard.

Expeditions of Amazing Adventure: The grasping overgrowth of Gymynda

Deep within the western forests was the famed city of Gymynda. Carved from the wilderness from pioneering humans, it established itself as a trading hub for the many tribes of the forest elves. A wary peace was struck long ago from the great elven chiefdom of Aldarianna Moonlight. Her wisdom and patience with the human settlement fostered a long relationship of mutual benefit and trade. At times relationships were strained, especially when some industrious humans of Gymynda struck out too deep within the territories claimed by elves, but her steadfast resolve for peace usually silenced any voices of violent reprisals.

Many claim it was her passing which sealed the fate of Gymynda. For many generations of cityfolk, the elven tribes were seen as good neighbors, even allies in times of need. However the Grand Chief Aldarianna Moonlight’s health began to wane from a mysterious illness. Despite the efforts of elven shaman and learned human healers of Gymynda, she slid further and further into a drifting malaise, as if her very life was being siphoned away. Within years she eventually succumbed and fell into a deep sleep and in days she had slipped from her mortal husk.

The death of their great leader was a time of long mourning within the elven tribes. The lead council of Gymynda also decreed a month of mourning among its citizens, but while the Grand Chief was respected, many of the folk within Gymynda did not hold the same reverence for her as those of her elven followers. Within a week mourning dress among the city dwellers began to lift and in short time life went back to normal. After all, many felt there was still coin to be made with trade, trapping, and farming, and some even felt it an ideal time to claim untapped ranges of forest for logging.

No one knows what caused the great growth. Some would claim it was a wicked curse brought about by elven shaman, to inflict their wrath on the humans that failed to show proper respect during the passing of their leader. Others say it was great magics wielded by the elven tribes to stifle the further expansion of Gymynda. Some state these elves knew with Grand Chief Moonlight now gone, the city would begin rampant expansion within their borders.

However a far more sinister tale is sometimes spoken. One of dark magics brought on by avarice from some within Gymynda, quite possibly a dark pact with demons to inflict a curse on Moonlight that would sap her very life force. A horrible spell with terrifying unseen repercussions.

For over a decade Gymynda prospered. The city grew and industry thrived. Great logging guilds reached deep within the thick woods. As the city developed, so did their men-at-arms and militia. The elven chiefdom broke apart as individual tribes had squabbled among themselves. Some sought peace, while many were willing to aid Gymynda in expanding into the lands of rival tribes if it meant keeping their holdings untouched. The wealth and affluence of the trading merchants and craftsmen guilds swelled within Gymynda. Gone were the days of hearty pioneers as opulent ways were adopted among the more wealthier citizens.

Then, on the sixth full moon of a new year, the cursed growth sprung up within Gymynda. Its citizens woke in horror to find buildings overgrown in thick vines. Young trees and grasses burst forth among cobbled stone streets. More terrifying was that some were found entombed in thick vines, suffocated and serving as a morbid bed of blood red flowers which covered their corpses. Efforts to hack away at the vines and trees were a herculean task. A man would go through several steel axe heads and only manage to make a paltry clearing. On the next morn they would find their efforts worthless, as new verdant growth would replace any cleared areas.

However all of these events paled to what soon followed. The denizens of Gymynda soon found themselves to be growing like the land around them. Patches of skin became covered in thick moss. Blood red flowers emerged from ears, eyes, and mouths. Bodies stiffened as their very limbs began to sprout tendrils of thick roots and vines.

Panicked people fled from Gymynda. Those that sought refuge with the elves were turned away or slain, the elves burning the bodies that remained with ritualized magics. The forest elves knew that dark primal magic was at play. Those that were afflicted could spread the sickness to others and they had to be held at bay through any means. Word of this spread to neighboring kingdoms, and when similar afflictions were seen among villagers that interacted with the stricken people of Gymynda, these lords also decreed to slay any that appeared from the forest.

A century later, some say the ruins of Gymynda can still be made out among the clinging wild of vines and trees. Some have claimed to have explored such ruins, but few can be believed. As to this day a shambling figure can occasionally be seen shuffling out of the forest edge towards neighboring villages, horrid creatures bent on engulfing large animals and man alike in tendrils of writhing vines.

Some village leaders adopt a proactive stance, encouraging adventurers to make expeditions within the deep forests and clear out any cursed beings that they may find. Some are even willing to pay coin for those that do. All the while, one can always manage to hear tales spoken after several pints in these village taverns. Tales of how sudden was the overgrowth that choked the life out Gymynda and its wealth would likely still be there, hidden under a carpet of moss and vines. All of it just waiting to be plucked up by those brave enough to enter within the cursed ruins.

Review: 13th Age

While it’s been available as a pdf for some time, the hardback rules for 13th Age from Pelgrane Press are finally getting to folks. For a long time I was on the fence about this. I was happy with my 4E game but the more I played, the more flaws with the game came up especially as my group leveled up. PC power glut was a big issue and I thought up a few potential tweaks to trim the list down. I even considered consolidating at-will powers and altering the basic attack to make it more attractive as an alternative. It sort of was swept under the rug compared to other at-will attacks for PCs. Lastly, I really wanted some way to give players an option of pouring out the damage, and considered using healing surges as a means to do so.

While it’s been available as a pdf for some time, the hardback rules for 13th Age from Pelgrane Press are finally getting to folks. For a long time I was on the fence about this. I was happy with my 4E game but the more I played, the more flaws with the game came up especially as my group leveled up. PC power glut was a big issue and I thought up a few potential tweaks to trim the list down. I even considered consolidating at-will powers and altering the basic attack to make it more attractive as an alternative. It sort of was swept under the rug compared to other at-will attacks for PCs. Lastly, I really wanted some way to give players an option of pouring out the damage, and considered using healing surges as a means to do so.

So last week I decided to take the plunge and pick up 13th Age. As I glanced through the rules, what I found particularly interesting was that most of the beefs I had with 4E seemed to be addressed with 13th Age. It’s not entirely surprising as one of the designers was also involved in creating fourth edition D&D. But I particularly liked how much of the glut of temporary modifiers and ever-expanding power choices in 4E were removed, making the game seem much more fluid and engaging.

13th Age is a high fantasy rule set based on the d20 system. No bones about it, I’ve heard this described as a love letter to 4E and I can totally see the imprint of that in the rules. What makes this stand out however, is how many good things it took from 4E, while dumping the extraneous bits, making for a slimmer, fun ruleset. Those at home with 3.5 will also find some familiar territory here, but I think more of the roots with the game are with 4E.

The game relies on many standard choices for races (dark elves are an option) and classes from past editions of D&D (no monks, druids, or shaman). Multiclassing officially is not part of the ruleset, but certain classes can definitely dabble in other class abilities with feats or domains. There is a bevy of your typical high fantasy monsters and a decent list of magic items.

It’s still d20 D&D here. You have levels, 6 ability scores ranked from 3-18, AC, hit points. A nod to 3.5/4E much of the mechanics revolve around rolling a d20 over a set DC value. As with 4E, there are specific defenses for spells and effects where players roll against listed physical or mental defenses. There is initiative and everyone attacks in that order during a typical turn.

Healing is very loose and liberal. As with 4E (and DnDnext) each class has a number of recovery dice that they use to recover HP. And as an action one recovery can be used during combat. Characters have death saving throws, and ample means to heal themselves. Clerics aren’t required, but their abilities definitely supplement the party’s healing potential greatly.

Similar to DnDnext, there isn’t a formal list of skills. Checks are made in a similar fashion, rolling against static DC values for easy, hard, and difficult checks. There are different main tiers, from adventurer, to champion, to epic with resulting DC, defenses, and attack bonuses from monsters and hazards scaling upwards. These are spread out from levels 1-10 however. Correspondingly monsters also have defenses, HP, and attack bonuses that scale up. However you will see certain creature types plateau. So don’t expect to see a variety of kobolds that range from level 1 to 4 like in 4E.

Character progression and advancement are familiar. Players add a level bonus to attack dice, skill checks, and defenses. Hit points increase incrementally, as do ability modifiers (resulting in some changes to defenses). Also a regular advancement of feats and spells are rolled out, resulting in every level bringing something to the player gradually increasing power and abilities. One particular change I like is that many class options don’t necessarily mean a brand new ability, but rather can improve on those they already have. While wizards and clerics can expect a new spell or two as they advance, most other classes will get more utility out of their attacks and abilities.

I’ve covered some things that are similar, now onto things that make 13th Age stand out. There are many aspects of the game that allow for character customization. Skills are not present, rather a player has so many points for backgrounds instead. These PC backgrounds highlight past experiences and history. If the DM thinks it has an application to the task at hand, they provide a bonus. It’s very freeform and supplements the simple ability score checks of the game well. There are a wide variety of feats that confer small bonuses and little tweaks to abilities.

This ties in very well to the abilities (read powers) of the character classes themselves. Many of the game mechanics revolve around the d20 roll. Some situational bonuses come about on a miss, rolling 16+ on the to hit roll, to hits that are an even result. This gives some varying situational benefits to combats. Feats expand on these abilities, giving some even greater effects when they trigger, or possibly adding more predictability to when they do. Because characters start out with a fair number of feats and continually expand on them, they gain a lot of customization. You can end up with two level 3 fighters that have very different abilities.

Another key aspect of combat is the escalation die. After the first round of combat a simple d6 continually goes up from 1 to 6, with the current value granting players a bonus to attacks. Monster abilities also can interfere with this. It’s a nice tool in preventing fights from dragging on and keeping the action moving, encouraging the combatants to be proactive. Combined with situational powers related to attack results, you have combat that is engaging and less about just a hit or miss result with attacks.

Combats are also very much within the theater of the mind. Creatures are either engaged or not. They are either nearby (within a standard move) or far. They are in cover, or not. Attacks of opportunity are there, but with a simple check, players can slip away if needed. Likewise, unengaged creatures can intercept others trying to slip around them. So there is some tactical movement, but nothing rigid requiring a grid to run a melee.

Leveling up is also fast and loose. No experience points are awarded. Rather, GM’s are encouraged to level up the PCs when they feel appropriate. A rule of thumb is after three to four major resting points players should advance a level. Each resting point is after 4 major fights. So after about twelve to sixteen melees, the players should have enough under their belts to level up. The focus of the game is when it’s dramatically appropriate though. So after achieving a major quest is perfectly acceptable too.

Magic items are split into two camps. Your mundane consumables in the manner of oils, potions, and runes that provide a simple mechanical bonus, and that of permanent items. The consumables are made to be your typical one use, throw away items that are actually rather mundane. Magical permanent items however are meant to be special and wondrous, each with a personality. You aren’t going to run into a simple +1 dagger but you will have one that has some history or quirks to it that encourages more story effects in the game.

Two additional points make 13th Age stand out from other RPGs, a player’s one unique thing and icon relationships. Every character will have one unique characteristic that makes them stand out from others in the world. It’s geared towards a background-centric or plot device, rather than some game mechanic benefit. This is decided at character creation and can be a relatively simple concept (they are the 5 times grand world champion of dwarven ale drinking) to something grander in scope (they are the long lost child of the Elf Queen). How this affects the game is something played out as campaign unfolds with input from both PCs and the GM.

The other major point is the concept of icons and the relationships PCs have with them. There are 13 icons within the game, each being an actual individual in the game world. Consider them the movers and shakers of the world, main factions and seats of powers that employ many agents within the world to do their bidding, and this includes the characters. Players can decide on their relationship with certain icons as being positive, conflicted, or negative. They start with 3 d6 and can allocate them as they will among the many icons.

Some may want a more prominent role within the circles of a particular world power, while they may want to be the bane of a certain 13th Age icon. At the start of the session, each player rolls their relationship dice and results of 5 or 6 (5 means there are more complications along with the boon) ensures that at some point in the game, the player will have assets of that icon at their disposal. That at some point, the icon (or agents on their behalf) will seek out the player and impart some timely advice, offer some resources, or potentially some task or quest for the player. It’s an interesting idea and very much helps drag the players into the world, ensuring they have the ear (or the wrath) of major powers within the game.

The Good – It’s a nice package for D&D. The mechanics are uniform, with enough working parts and customization to make for a fun game. I think it would be very approachable to new players. Elements of the game are familiar with enough small situational conditions to make combats enjoyable and move well. I particularly enjoy how most of the fiddly bits for combats are swept aside and more emphasis is on the players pulling off big moves or big hits. The game encourages the players to engage the GM and be part of the overall story. Best of all, everything needed to play is in a single book.

The Bad – It’s D&D. You have HP, AC, attack bonuses, nothing here that is completely groundbreaking. The aspect of the 13 icons in the world are interesting, but that does add some limitations to the game fluff. Your default setting is high fantasy and revolving around these major world powers. You can totally go off the rails and make your own, but this will take some effort to ensure all the player options fit well with your custom icons.

The biggest damning aspect of the rules is while I think a new player could get the gist of the game very easily, it does require an experienced GM. The icon relationship dice mean as a GM you have to be willing to improvise and be flexible with the story you are telling. While some of the mechanical aspects (skill checks, level appropriate monsters and challenges) are well laid out and understandable, there is a lot more skill needed to running an effective session. This hurdle is recognized in the rules, but I think it also is a major detraction to the game. YMMV with this game as how well a GM can weave in the icon relationships during a session is key.

The Verdict – 13th Age is a good game. I think it’s very much a great introduction to fantasy RPGs and if someone wanted to play ‘D&D’ you could do well with pulling this book out instead. For fans of 4E and 3.5E, both will get a lot of enjoyment out of the rules. It has familiar aspects of play with enough wrinkles to make it enjoyable. If anything, this could certainly be considered for 4E fans a nail in the coffin for starting up another 4E game.

It’s not perfect. There are major default setting choices with the game. It’s one of high fantasy. You have established movers and shakers in the world. It is entirely a game of heroic adventurers (level 1 farmer peasants need not apply). But if you want to play a game where you are big damn heroes, destined for greater things, and well-connected to the pillars of power, 13th Age is for you.

There is a lot here that works. Play and options are streamlined enough to not be overwhelming, but still offer some customization. What I particularly enjoy is that there’s a balance between simple mechanical bonuses and others related more towards the story of the character. You don’t have a simple diplomacy skill, you have a strong background in the Emperor’s royal court. You don’t have a skill in tracking, you were a lead scout for a barbarian warband in the last goblin war. This stuff oozes with story and fodder for adventures. Along with the one unique thing about your character, you have something that stands out from other RPGs, giving a more interesting spin on character creation than what’s seen in other games.

One very strong point about 13th Age is that everything needed to play is covered in one single book. It’s a low entry into RPGs and something akin to Pathfinder. I will say it can be tough to justify buying 13th Age if you are heavily invested in other fantasy RPGs. Nothing here is absolutely groundbreaking and it falls heavily back on a very familiar d20 system. Between the different camps of D&D, I think 4E fans might enjoy this a tad more. As for people into Pathfinder and 3.5, they may very well like the more streamlined character creation, uniform mechanics, and opportunities for dynamic (at times chaotic) combats. There is a strong emphasis for story and weaving the PCs into the world, much more so than in some other systems. But like any RPG, it does come down to the DM and how much they can make the game fun for all involved.

My final take, 13th Age is a good buy. It has some interesting concepts you could lift for your own game, however it might tread a bit too much on the familiar for some. This is a d20 D&D game. For some it could be very well their ONLY D&D game. As a big 4E fan, if I were to jump back into D&D, this would certainly be my game of choice. It’s a tad rigid for the setting and requires a more dynamic approach to planning out your sessions, but there are some fun things in between the pages of the rules to make it worth your time.

Improvising 4E encounters

At first I was a bit hesitant about creating encounters on the fly for 4E. I slipped into this mindset about planning everything out. While I still feel combats in 4E worked much better as set pieces, at times PCs might go off into another completely different direction. When they did that, I felt combat likely shouldn’t be an option as I just wasn’t comfortable enough creating something up on a whim. I wasn’t sure if it would be challenging enough (or too difficult).

What I failed to notice was that the monster math in 4E was very open to DM. It just took some effort to sit down and work it out per level. It was deceptively hindering at first but when you really looked at it, you saw how simple and elegant it was.

Then there was the Sly Flourish DM sheet, where the guy did what we all should have done at the beginning, just create a spreadsheet that does the math and print it out. Granted this was using adjusted HP and damage with the ‘updated’ monster stats, but it laid out how simple creating monsters were.

The DMG did have a similar table but required a little calculation. Still if the effort was made, you could instantly create a challenge appropriate fight for PCs. All that was needed were a few keywords for damage types and you had the core of an interesting monster.

I really think one of the biggest flaws in presenting 4E was not including a fully sketched out table like this. Also not really providing more monster themes was another failed opportunity. Maybe they wanted to hide how easy this all was. That in a flash, you could make up custom monsters with damage, HP, attack bonuses, and defenses that would be level appropriate.

Honestly, I’ve found the openness of the entire nuts and bolts of the game refreshing. You could pull things apart, cram things together, and 9 times out of 10 it would work fine. The elegance in being able to quickly create encounters just worked so well. It’s something few folks are willing to admit, that 4E gave the DM a lot of tools and freedom to make really cool stuff. I don’t think I ever really bothered making up custom monsters with older editions like I did with 4E. Best of all was that it worked very well.

Sadly I don’t think this was ever really explored more, and I wish more emphasis was placed on the DM taking stuff like this and running with it. While it was great having pre-made monsters and traps the idea you could whip up your own in a snap should have been promoted more. It’s one of the elements of 4E that made it my favorite edition.

4E must have books

I expect the footprint of 4E will be getting smaller and smaller in stores and in the convention scene. However I won’t be surprised to see some retailers trying to dump existing stock before DnDnext rolls out. If you were inclined to pick up some books for a 4E game, what would you get? There are a lot (over 30!) hardback books to choose from, not including adventures, some other smaller softback books, tiles, and such. So if you were to dip your toe into 4E and pick up some books on the cheap, what would be a short list of must buys?

As for myself, I may be potentially making a move and really need to consider what books to hang onto. Looking over my D&D library if I wanted to run a 4E game in the future what books can I dump and which ones should stay on the shelf? A while back I thought up a list of books needed to run a long term game, so what would I change given the newer releases since then?

Core Essential Buys – Immediately I would split off into 2 branches, and each I consider exclusive of the other. Either you go Essentials or go with the older core 4E books. Essentials and original 4E are the same game. You should be able to plug and play any of them into your game. However you might run into some subtle differences with character progression between the two. That’s why I’d consider if going the Essentials route, it’s best to stick to that entirely for core books.

So if going the Essentials route, I’d pick up Heroes of the Fallen Lands, Heroes of the Forgotten Kingdom, Dungeon Master’s Kit, and the Essentials Monster Vault. I have not gotten some of these books, however I consider them solid choices to easily gather core components of a 4E game together in a short stack. The are designed to complement each other with the rules. So having these you should have enough to run 4E.

The alternate is going the more traditional route of the older hardback books. I tend to think that if you wanted to expand your collection with a few additional books, this might be the better route. With that, I would pick up PHB 1 and 2, the DMG, and the Essentials Monster Vault.

You’ll notice I didn’t mention the original Monster Manual. Sadly, I think it is retired to the ‘stuff not to bother with’ list. The Essentials Monster Vault is a better product. The monster math is fixed and you have a book of core monsters that should be good for your campaign. Not to mention the loads of great monster tokens in the box.

With going either of these branches, you’ve got tons of material for your game and likely never need another book.

Solid Buys – If you wanted to add a little to this stack, there are 2 the additional books I would consider picking up:

Monster Manual 3 – It adds more monsters and even better fit in with the updated defenses, HP, and damage to challenge the players. I like the idea of no fuss monsters where I don’t have to spend a lot of time tweaking them. This book provides that.

Mordenkainen’s Magnificent Emporium – More magic items are a bonus and this book covers the gambit. It includes some adventure seed ideas (detailed magic item backgrounds and cursed items). Not to mention rounds out some much needed potions. It also fits well with either your original core 4E books or the Essentials line.

Good things to pick up later – There are a few books I would move into the stack of books to hang onto (or potentially pick up). These aren’t needed and some are more aligned with particular books, but they make for some good choices to expand your game:

Essentials Rules Compendium – It’s an extremely handy reference for your table. If you are one to regularly hit the convention scene or game on the go, even more so. However I tend to think that 4E will become more of a niche game in the future and likely not be seen too much in conventions. Still it is a decent, quick, go to reference to have at your table for rules.

AV vault 2 – I would only consider picking this up if you’ve got the Player’s Handbook 2. More magic items are always nice and the additional class specific items make it a decent addition to your collection.

Campaign specific player books – 4E went the route of having a player-centric and dm-centric book for both Eberron and Forgotten Realms. I’d consider getting these books if you were interested in jumping into these settings. Fortunately, Dark Sun went the route of packaging all of that into one book. While they are campaign setting specific, all 3 allow more player options to the game.

For a DM getting just the campaign setting material isn’t worthwhile. With enough digging on the internet, you can likely wrangle up enough information from online resources to run a game (maps, general location information, etc.). It’s the player rules specific to 4E that are lacking, and these books do the trick.

Stuff not to bother with – Everything else. Yup. You are now delving into territory that I consider either very campaign specific or stuff that’s peripheral to your game. Between PHB 1 and 2, you’ve got a ton of character options. Unless you were playing new campaign of the month, I seriously doubt that your players would want to dig into the options of the power source books. Some of the planes books and others like the Underdark are nice, but again very campaign specific. You can definitely mine these for adventure ideas however I would easily consider them not worth picking up. While it might be nice if you wanted to keep, or obtain, a collection of 4E books, I think it best to just let them go and keep your gaming library lean.

So this is a short list of books I think would be needed if you wanted to run a 4E game. Just about 4 books. Four books to give you enough for years of 4E enjoyment. So if you want to clear out your shelf space and make room for DnDnext, or are thinking about picking up some 4E books on the cheap, this isn’t a bad way to start.

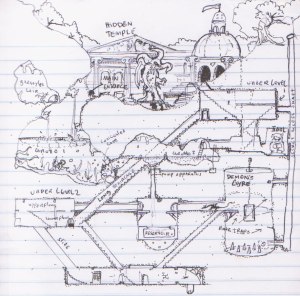

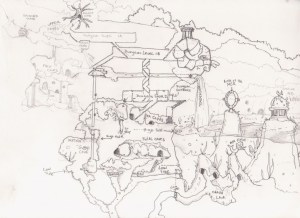

Throwing out the dungeon corridor

I grew up old school with AD&D. Scrawling out huge dungeons on graph paper was always an entertaining pastime, even if many of the lairs I drew never saw the game table. It was just a fun creative exercise to line up rooms and try to interconnect them all. This is something I have clung to over the years. Then of course I see some gorgeous freeform maps from Fearless DM and after picking my jaw up off the floor, come to the realization that trying to get something like this mapped out in its entirety would likely be an insurmountable task.

Something dawns on me, why bother mapping out the interconnecting bits? Why etch out on paper that you’ve got a hallway that goes 30’ and then branches into a T, heading east and west, each going another 40’ ending in at a set of doors? Why mess with all that detail?

Instead, just concentrate on mapping the rooms. The stuff with monsters in it. Where all the action is taking place. That is the meat and potatoes for just about any dungeon jaunt. Why bother trying to accurately get a layout for the entire network of corridors and hallways that interconnect everything? Why not just stick to getting the details set for where the players will be actively adventuring.

With that mindset, maps like these become more manageable and something easier to work with. In the past I occasionally would just handwave the layout of a dungeon. Now I’ve been doing it exclusively. I try to keep a framework of room connections through lines and intersections with a few notes, but it is all a rough sketch. I save the actual mapping for where encounters will be.

I’ve been liking this as it’s been making my adventure planning more modular and dynamic. So the group has been through a series of monster encounters. At the descriptive intersection they head left towards another combat, where heading right would lead them to a trapped room. I’m able to switch out the rooms and give my players something else to tackle aside from another hack and slash fight. Best of all, I don’t have to muddle around with trying to keep every interconnecting hallway accurately mapped out.

It gives me some options to make encounters more interesting also. Now I can throw monsters coming in from two directions when the party stumbles into a room (including from behind). Keeping the rooms networked together with a narrative description gives me some wiggle room. If I keep things general and tell the group they’ve gone through a series of corridors which head into a large chamber, that allows me to plop in monster reinforcements right in the direction they entered the room from. It helps keep the players from being complacent and too overconfident of their tactical situation in an encounter.

I’ve been liking this so much I’ve thrown out the idea of mapping out hallways. Just leaving things as a rough networked sketch has been great. It’s made it mentally easier for me to keep rooms dynamic and eased the ability of switching things around on the fly. Even better, when I see inspiring stuff like the maps here I’m more likely to use it and not worry about keeping in the corridors.

( Sadly, Fearless DM wrapped up his blog (where I snatched up these wonderful maps), but you can usually find him still dispensing RPG gems via twitter: @pseckler )

Obsidian Portal Kickstarter wrapping up

|

| A possible dashboard layout. Spiffy! |

I’ve frequently gushed on this blog how much I love Obsidian Portal. In fact, I’ve been a fan of the site for a long time. It’s been very functional over the years however I understand the people running it really want to give it a face lift.

A Kickstarter campaign is wrapping up in a few days. Fortunately, they’ve made their funding goals and then some. I’ve been a freebie user for a long time and I appreciate Obsidian Portal allowing that. If you aren’t a regular subscriber to their system this kickstarter is a great way to support the site.

So I hope folks are willing to send a few dollars their way. The project is funded. It’s a nice way to thank them for all the support they give to the gaming community. There are only 5 more days until the campaign ends, so if you are inclined be sure to support it soon.

Skill challenges revisited – Part 2

Last time I talked a little about how I design skill challenges for 4E, and this time I’d like to go through some things I do when running them. As a short summary from the last post I’d always consider what failure brings, and what a partial victory would bring. This partial victory is a step below a fully overcoming the challenge. Lastly I’d have 2-3 ideal skills that would grant a bonus or an easier DC to checks, but not have a hard list of skills required for the challenge.

Use markers for success and failure – I have a stack of black and white baduk (Go) game pieces handy. During a challenge while I describe the results of the PC’s actions, I also hand out either a white (success) or black (failure) bead. It’s a small hint to the players they are on the right track for completing a challenge, and they can quickly determine the relative amount of successes and failures they have.

This is also a decent way to keep track of a longer skill challenge. If you have a challenge that is interspersed with encounters and other events, it’s a nice means to record their progress. You can always keep this information hidden and simply give them some feedback for the task. However having this simple prop relays how poorly or how close they are to succeeding.

Don’t give out the hard numbers – Like in a combat with offering HP totals and AC values, I don’t tell players they need X amount of successes before Y number of failures. I also don’t give the players target DC values. I will offer players some description how difficult a potential action might be, especially for high DC checks (ex. ‘You could possibly make a running jump across the bridge, but it will be exceedingly difficult’).

If you approach challenges with hard numbers and set DC values relayed to the players they’ll pick up on this. Keeping things to a narrative curbs the metagaming. I don’t mind offering a tally of failures and successes, but the unknown variables of how to tackle the challenge should avoid set values given to the players. This way the group has to make that choice of going all in or deciding to cut their losses if things go sour.

Everyone participates – The PCs can’t sit idly by and let one player do all the heavy lifting. They all have to try and contribute to tackling the problem, even just by using the assist another action. Most challenges I run go through rounds. At the end of each round players either win (including a partial victory) or they fail. Note that time can stretch out for hours to days if needed between each ‘round’ but the important thing is (like a combat) that everyone has an opportunity to do something.

Say, then do – I get all the players to first tell me what they are doing, or trying to do, in the challenge. Once I get it all in my head I figure out applicable skills and checks needed. Then everyone rolls. I determine successes and failures, line up the action for the next round and repeat the process. Get your players to narrate what they want to do first. Frequently you’ll have one player initiate the action with other PCs sort of metagaming to see the outcome, and then adjust their plans. I like everyone talking about what they want to do first, and then see if things work out.

Be flexible – If a player thinks of a really clever way to use Athletics during a negotiation challenge, I’ll let them do it at least once. Be accommodating to cool ideas. You want to encourage players to think of creative solutions to the challenge and pigeonholing them to specific skills won’t help. As mentioned though, I usually will let them make a check with an oddly applied skill once, then rein in any repeats (or bump up the DC to a horrendous amount). Still if your PCs pull out a fantastic idea for using a skill in a way you haven’t thought of, at least allow them to try for a check.

Don’t be a slave to the challenge structure – Ideally there should be a certain number of successes or failures before the challenge resolves. If things progress to a closure earlier, don’t force more checks to be made. There may come a point where your players make some sound arguments to influence some NPC. If they nailed it, don’t drag out the challenge, just award them a victory and move on (partial victories work wonders in this case).

Sometimes you might have PCs do something amazing (or pull a bone-head move). If so, consider awarding more successes or failures to them for that check. Alternately you can think about giving the player a huge bonus (or a penalty if needed) for the next check. As mentioned in the previous post, consider skill challenge rules as guidelines. It’s applicable to both designing and running them.

I hope these tips help DMs run skill challenges. While clunky at times, with enough under your belt you get a feel for how flexible they can be. All the while skill challenges provide a framework for resolving and rewarding great roleplaying. Don’t be intimidated with them and try to use them in your game.

Skill challenges revisited – Part 1

I’ve always been a fan of the concept of skill challenges. I like the idea of having some means of awarding XP for roleplaying and not just saddling it to some interpretive standard. Skill challenges in 4E really offered a DM some decent guidelines for doing that. Better yet, skill challenges laid out a way to offer XP to players for great roleplaying aside from your typical hacking up monsters and completing quests.

I’ve always been a fan of the concept of skill challenges. I like the idea of having some means of awarding XP for roleplaying and not just saddling it to some interpretive standard. Skill challenges in 4E really offered a DM some decent guidelines for doing that. Better yet, skill challenges laid out a way to offer XP to players for great roleplaying aside from your typical hacking up monsters and completing quests.

Skill challenges were far from perfect however. I think what stood out for me the most was how they were more a framework of rules when running them. In the past few years I began to tweak with designing skill challenges and altering how I ran them. After a while I sort of fell into a groove running them by getting input from all the players and keeping the challenge structure fluid.

It’s been awhile since I visited skill challenges, so I figured on posting a bit on some approaches I use with designing and running them. It can be tricky, but once you get some concepts down regarding them, they are a snap to make up and run. Onto some tips:

Rules are a framework, not set in stone – I think something important to remember at the onset is that skill challenges work best approaching their structure as a guideline rather than a hard set of rules. It’s easy to stick to difficulty labels and outcomes based on X successes before Y failures. It’s far better to be flexible with running them. You may get a stellar idea from a player. Why not offer them 2 successes (or even pass it immediately)? If you adhere to a set format unerringly, challenges can feel artificial and constrained.

Start with failure – When first thinking up a skill challenge, start with thinking about what happens when the PCs fail it. Do you have something interesting happen? Is there a way to keep the story moving? If the answer is no, then don’t make it a skill challenge. Failure should always be a possibility.

Say you decide players have to progress in some underground tomb by opening a sealed door. Sounds perfect for a skill challenge, right? If they open the door great! If not, then what happens? If the answer is the players turn around and go back to town, the adventure is over, rethink making it a skill challenge. In some cases you have situations that give the story a hard stop and moves everything off into another direction, but if that’s the case a skill challenge likely isn’t appropriate (you’ve got a major story branch instead). You should always consider what happens if the players fail a skill challenge and have an alternate plan.

In the above example failure might mean the players do bypass the door but one of the PCs gets severely injured. Maybe the door suddenly closes and the group is split up. Maybe they can’t open the door and instead have to go some other route that is longer or more dangerous. In each case the group can continue on with exploring the tomb, but have varying penalties and unfortunate circumstances due to failing the challenge. Make sure that failing the challenge doesn’t halt the adventure.

Have gradations of success – A partial success for a skill challenge should allow the players to squeak out a win. I typically set this as 1-2 less successes needed from the total to win the challenge. If they do this they are successful for the challenge but get ½ the experience reward. Think of this as a victory with some complications, or no clear advantage despite overcoming the challenge.

The alternate is a complete victory with the challenge. The players push themselves to get the required number of wins. Not only do they complete the challenge and get the full XP awarded but they will get some kind of advantage or benefit.

With the above door opening example, let’s say a failure means the party has to take a more difficult route. A complete victory means the players open the door and possibly can skip a potential encounter. A partial victory would then be in the middle of the two. Yes, the players get through the door but maybe they trigger the attention of some monsters. Maybe it’s a very difficult and taxing physically, so all the players lose a healing surge. While they complete the challenge, it’s not without some additional hardship.

Use preferred skills, not absolute ones – I think another trap to avoid is having a list of skills that are absolutely needed for the challenge. Instead you might want a short list of skills (2-3) that have an easier DC, or confer a small +1 bonus when utilized for the challenge. Additionally, I’d consider these as skills other players can utilize to assist another player. I’ll get a bit more into this with part 2, however giving a laundry list of checks for the players to select from is boring. Instead, you should be flexible with what skills can be used.

If players have to convince a Duke to release garrisoned troops to prevent a warband of orcs from heading through a pass, diplomacy might be a key skill for such a challenge. I’d figure that trying to reason with the Duke is a likely course of action and grant a +1 to using this skill for the challenge. But let’s say a player wants to use intimidation? If it’s not on the list of needed skills could it be used? Would intimidation be an automatic failure (after all I am seeing diplomacy as a key tactic)?

How about that player wanting to intimidate the Duke states they dig through a sack and produce the head of a slain orc. They throw it at the feet of the Duke and state this is what’s coming for the village. The orcs will likely do the same to him, his family, and all the common folk, hack off their heads and keep them as trophies. Locking yourself into a set list of skills required for a challenge will very likely also mean being inflexible when players give you a surprise like this. Give them some freedom to use different skills, and that starts by not demanding specific checks be made.

That’s it for now. In my next post I’ll go with some nuts and bolts with how I run challenges.

Give DnDnext dials that go up to 11… and ways to turn it down to 8

One aspect that seems to be common in the buzz surrounding DnDnext is modularity. It seems that lots of alternate rules are in the plans. I think that’s a good thing.

Other rule sets dabble in this and it’s something I’ve always appreciated. Granted, I think just about everyone home rules their game a little. Yet I think for new DMs having some guidance is especially beneficial. It’s great to have these core rules, with a few sidebars of suggestions and alternate rules to make the game more complicated (or make things easier).

One thing that stuck out for me with 4E was the lack of official nods towards tweaking the game. While I always got the DM philosophy with 4E being, ‘It’s your game, make it the way you want’, having some options in the books would have been helpful. And the rules that were there could have been emphasized a tad more (pg. 42 DMG). You had this whole debacle of skill check DCs being high, then being cut in half, then shifting up to being close to the original values. Having additional ways to fiddle with the game would have done wonders in addressing errata for these codified rules.

I’ve always liked having the developers provide some suggestions on ways to tinker with the game. It saves me time having to think up and test out my own ideas when I could be spending that playing games. Plus I think having rules that are more fluid to different play styles gives the game room to appeal to more people. For organized play this can be an issue, however it’s something that can be worked around (there is always that option of using a ‘vanilla’ set of rules if needed).

One thing I am hoping for however, are not just ideas and tweaks to add complexity and make the game more challenging to players. There should also be options to streamline the game more and beef up PC power. While the core base of the rules should provide a challenge to PCs by default, having some options to put on the kid’s gloves would be nice. Some groups may not be full of super-optimized character builds and having the game locked into that default setting for mechanics can be problematic.

4E had encounter building pretty solid, however as the game progressed with different player options I think it began to slide towards altering core monsters to provide a challenge. It seemed the game sort of straddled trying to cater to the needs of power gamers and other groups with less optimized characters. The math of the game grew into being built around PCs having defenses of X and attack bonuses of Y at level Z. If you opted to work on other stats, you sort of shot yourself in the leg with player advancement. So having options of turning down the game difficulty should not be overlooked.

Either way, it looks like the intention of DnDnext will be to cover a lot of different play styles over a core framework of rules. A sound decision over just creating one base set of rules that tries to cover everything.